09 JUL 2020

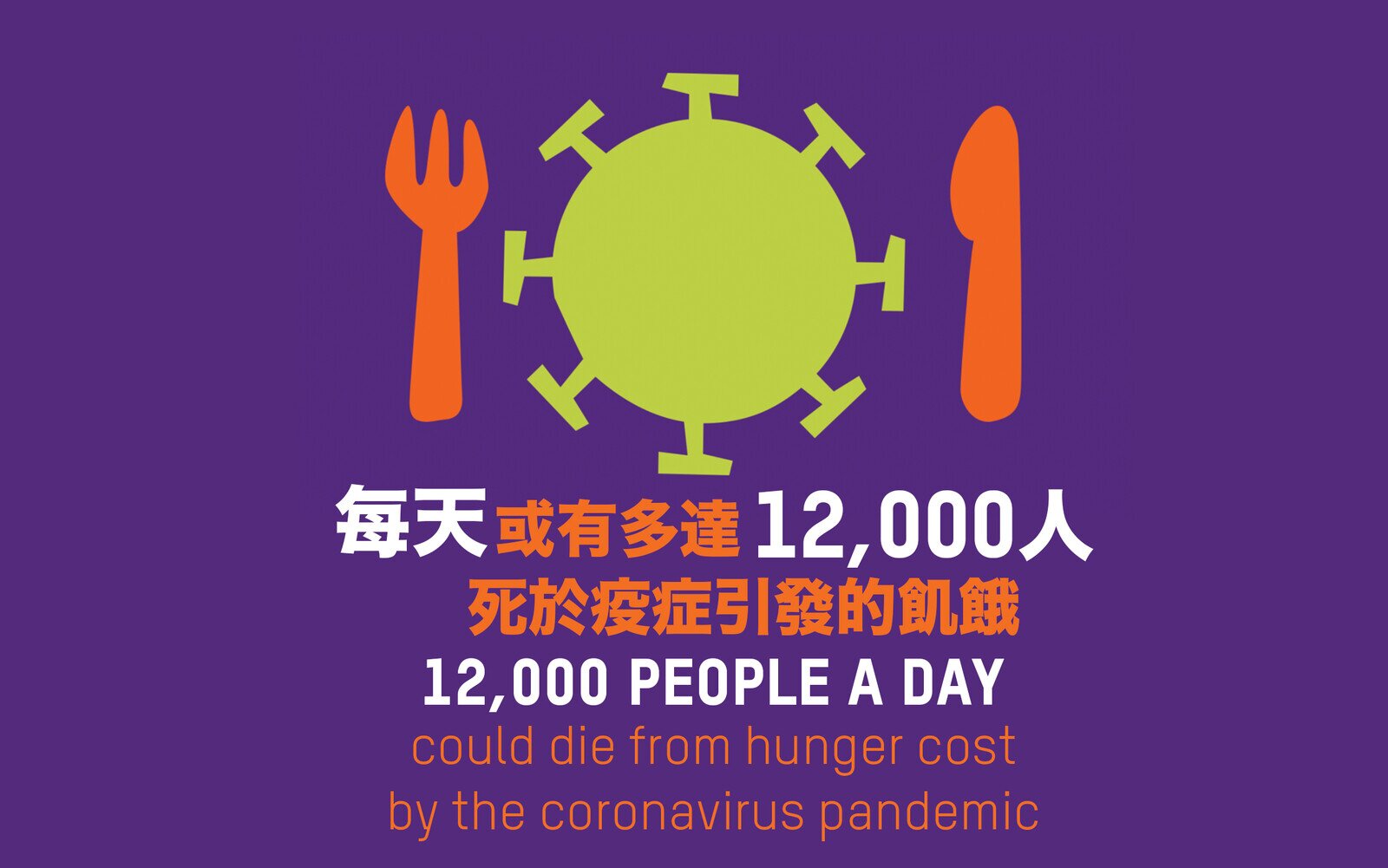

12,000 people per day could die from COVID-19 linked hunger by end of year, potentially more than the disease, warns Oxfam

Eight of the biggest food and beverage companies pay out US$18 million to shareholders as new epicentres of hunger emerge across the globe.

As many as 12,000 people could die per day by the end of the year as a result of hunger linked to COVID-19, potentially more than the number of people who could die from the disease, warned Oxfam in a new briefing published today. The global observed daily mortality rate for COVID-19 reached its highest recorded point in April 2020 at just over 10,000 deaths per day.

‘The Hunger Virus,’ reveals how 121 million more people could be pushed to the brink of starvation this year as a result of the social and economic fallout from the pandemic including mass unemployment, disruption to food production and supplies, and declining aid.

Oxfam’s Interim Executive Director Chema Vera said: ‘COVID-19 is the last straw for millions of people already struggling with the impacts of conflict, climate change, inequality and a broken food system that has impoverished millions of food producers and workers. Meanwhile, those at the top are continuing to make a profit: eight of the biggest food and drink companies paid out over US$18 billion to shareholders since January even as the pandemic was spreading across the globe – ten times more than the UN says is needed to stop people going hungry.’

The briefing reveals the world’s ten worst hunger hotspots, which includes places such as Venezuela and South Sudan where the food crisis is most severe and getting worse as a result of the pandemic. It also highlights emerging epicentres of hunger – middle income countries such as India, South Africa and Brazil – where millions of people who were barely managing have been tipped over the edge of the pandemic. For example:

- Brazil: Millions of poor workers, with little in the way of savings or benefits to fall back on, lost their incomes as a result of lockdown. Only 10 per cent of the financial support promised by the federal government had been distributed by late June, with big business favoured over workers and smaller more vulnerable companies.

- India: Travel restrictions left farmers without vital migrant labour at the peak of the harvest season, forcing many to leave their crops in the field to rot. Traders have also been unable to reach tribal communities during the peak harvest season for forest products, depriving up to 100 million people of their main source of income for the year.

- Yemen: Remittances dropped by 80 per cent – or US$253 million – in the first four months of 2020 as a result of mass job losses across the Gulf. Borders and supply route closures have led to food shortages and food price spikes in the country which imports 90 per cent of its food.

- Sahel: Restrictions on movement have prevented herders from driving their livestock to greener pastures for feeding, threatening the livelihoods of millions of people. Just 26 per cent of the US$2.8 billion needed to respond to COVID-19 in the region has been pledged.

Women, and women-headed households, are more likely to go hungry despite the crucial role they play as food producers and workers. Women are already vulnerable because of systemic discrimination that sees them earn less and own fewer assets than men. They make up a large proportion of groups, such as informal workers, that have been hit hard by the economic fallout of the pandemic, and have also borne the brunt of a dramatic increase in unpaid care work as a result of school closures and family illness.

‘Governments can save lives now by fully funding the UN’s COVID-19 appeal, making sure aid gets to those who need it most, and cancelling the debts of developing countries to free up funding for social protection and healthcare. To end this hunger crisis, governments must also build fairer, more robust, and more sustainable food systems, that put the interests of food producers and workers before the profits of big food and agribusiness,’ added Vera.

Since the pandemic began, Oxfam has reached 4.5 million of the world’s most vulnerable people with food and clean water, working together with over 340 partners across 62 countries. We aim to reach a total of 14 million people by raising a further US$113 million to support our programmes.

Notes to editors

- Download 'The Hunger Virus: How the coronavirus is fuelling hunger in a hungry world'.

- The WFP estimates that the number of people in crisis level hunger − defined as IPC level 3 or above – will increase by approximately 121 million this year as a result of the socio-economic impacts of the pandemic. The estimated daily mortality rate for IPC level 3 and above is 0.5-0.99 per 10,000 people, equating to 6,000-12,000 deaths per day due to hunger as a result of the pandemic before the end of 2020. The global observed daily mortality rate for COVID-19 reached its highest recorded point in April 2020 at just over 10,000 deaths per day and has ranged from approximately 5,000 to 7,000 deaths per day in the months since then according to data from John Hopkins University. While there can be no certainty about future projections, if there is no significant departure from these observed trends during the rest of the year, and if the WFP estimates for increasing numbers of people experiencing crisis level hunger hold, then it is likely that daily deaths from hunger as a result of the socio-economic impacts of the pandemic will be higher than those from the disease before the end of 2020. It is important to note that there is some overlap between these numbers given that some deaths due to COVID-19 could be linked to malnutrition.

- Oxfam gathered information on dividend payments of eight of the world’s biggest food and beverage companies up to the beginning of July 2020, using a mixture of company, NASDAQ, and Bloomberg websites. Numbers are rounded to the nearest million: Coca-Cola (US$3,522 million), Danone (US$1,348 million), General Mills (US$594 million), Kellogg (US$391 million), Mondelez (US$408 million), Nestlé (US$8,248 million for entire year), PepsiCo (US$2,749 million) and Unilever (estimated US$1,180 million). Many of these companies are pursuing efforts to address COVID-19 and/or global hunger.

- The ten extreme hunger hotspots are: Yemen, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Afghanistan, Venezuela, the West African Sahel, Ethiopia, Sudan, South Sudan, Syria, and Haiti.

Please support Oxfam's Coronavirus Response appeal